Protest and the Arts

Thirty-six years ago, I attended my first protest. Compared to the horrific events unfolding today, it might seem almost quaint, but as a second-year student at the Corcoran School of Art, it mattered deeply to me and my classmates. We were protesting the Corcoran Museum’s last-minute cancellation of a photography exhibition by Robert Mapplethorpe.

To set the stage: at the time, the “Moral Majority,” led by Jerry Falwell and reinforced politically by figures like Senator Jesse Helms, had assumed the role of policing art and anything they deemed morally suspect. Their agenda included opposition to media outlets accused of promoting an “anti-family” message, resistance to the Equal Rights Amendment and arms-limitation talks, rejection of state recognition of homosexuals, prohibition of abortion all abortions, support for Christian prayer in public schools, and active proselytizing of Jews and other non-Christians.

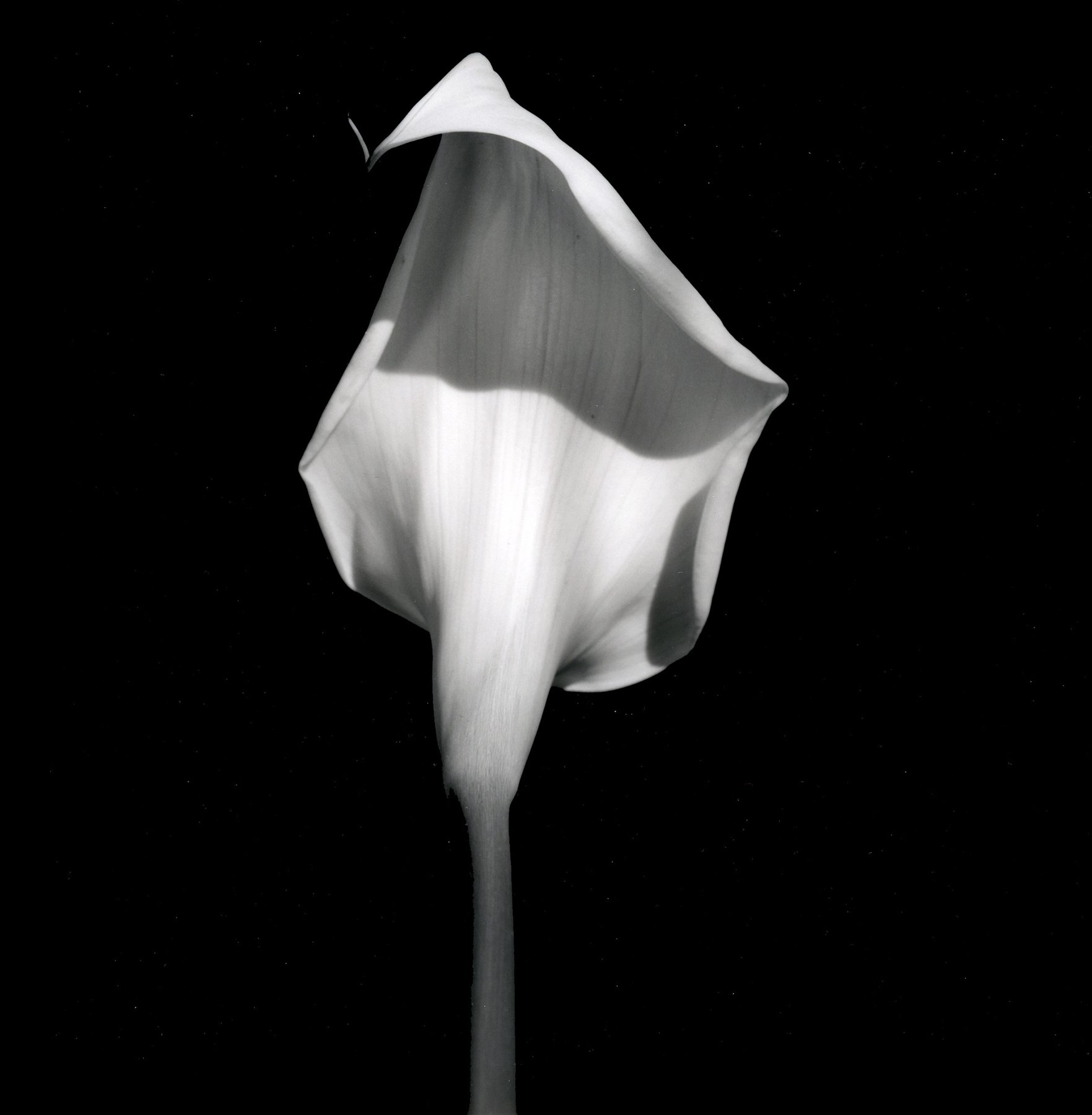

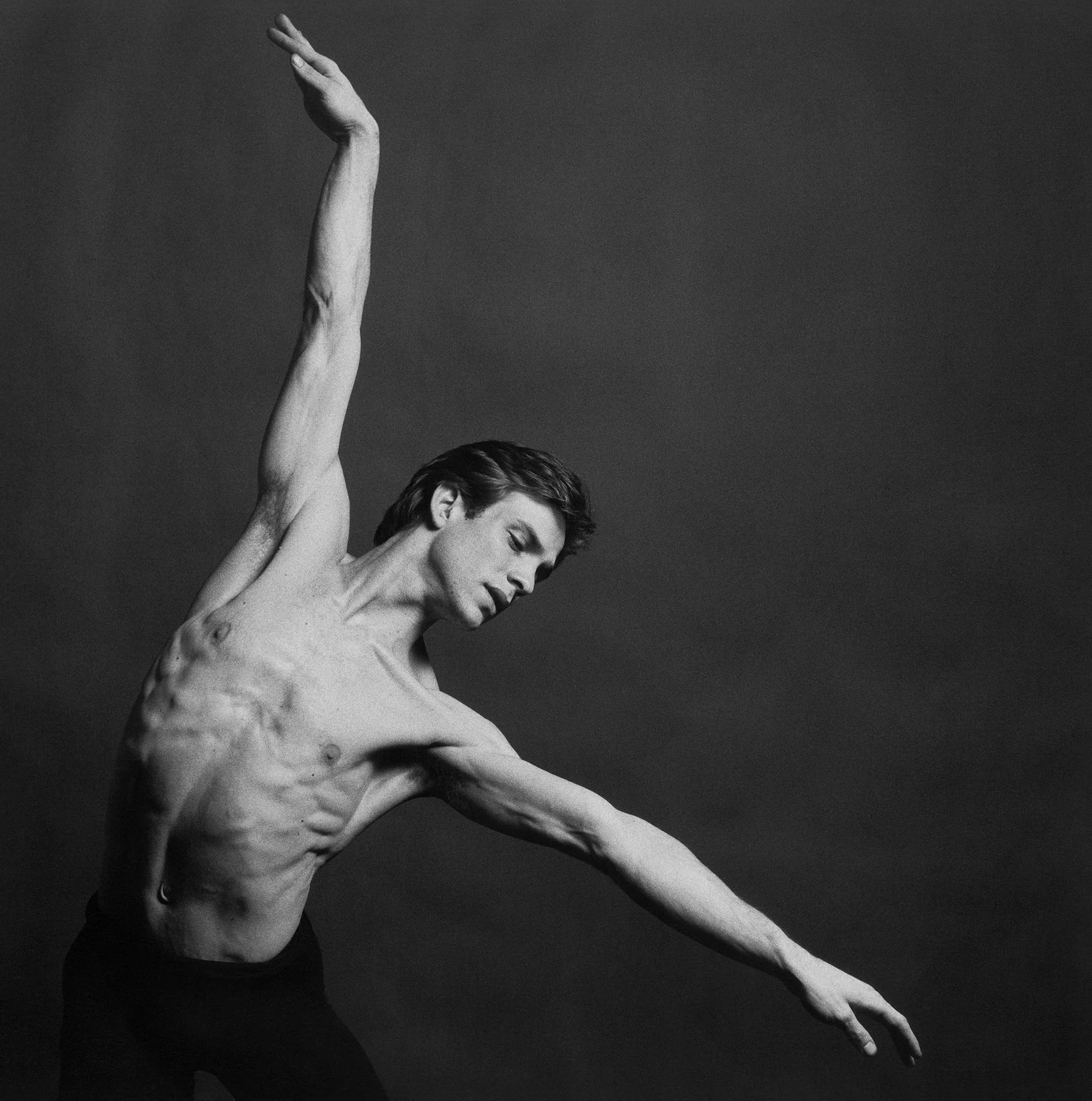

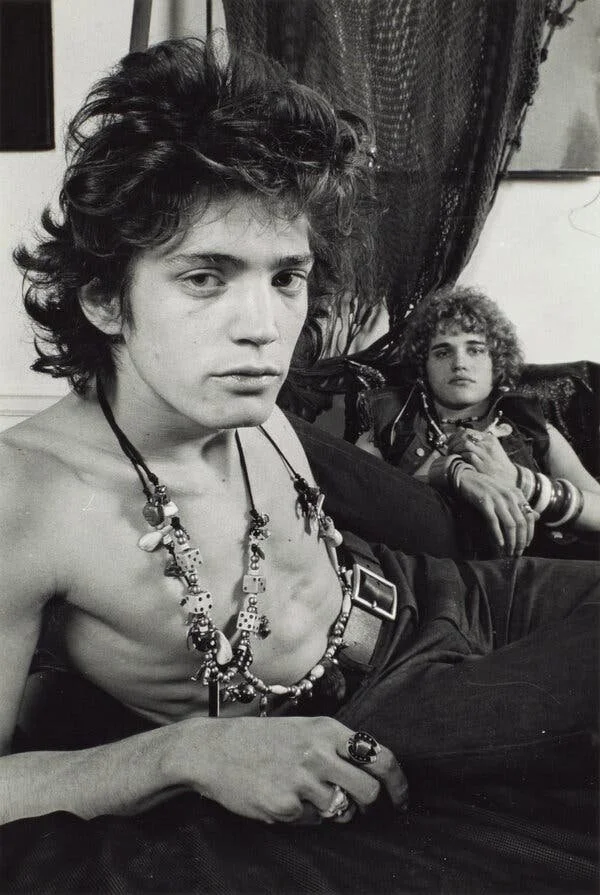

Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS that same year, was already a celebrated photographer. His stark black-and-white images ranged from celebrities to flowers, from classical nudes to some of the most controversial photographs of the gay male BDSM subculture in New York during the late 1960s and early 1970s. I remain a huge admirer of his work.

Our protest was modest. There were no threats of retaliation, no financial risk to us personally. We were simply standing outside saying, This isn’t right, and it wasn’t. Many of us believe the Corcoran’s decision became an original sin from which the institution never fully recovered. Fellow artists canceled D.C. shows in solidarity, gallery members withdrew their support and hundreds of protestors gathered in front of the Flagg Building, across from Ronald Reagan’s White House, to register their disapproval. In the months that followed, donors large and small redirected their money to other worthy institutions, of which Washington has plenty.

Calla Lily, 1988 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

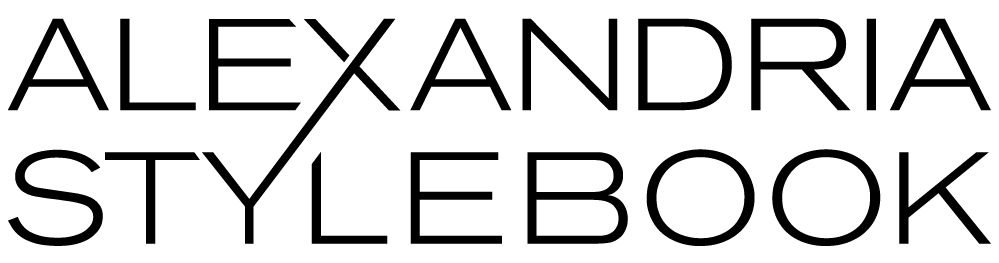

Ken Moody and Robert Sherman | Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, 1993

Two Men Dancing,1984 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

Marcus Leatherdale, 1978 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

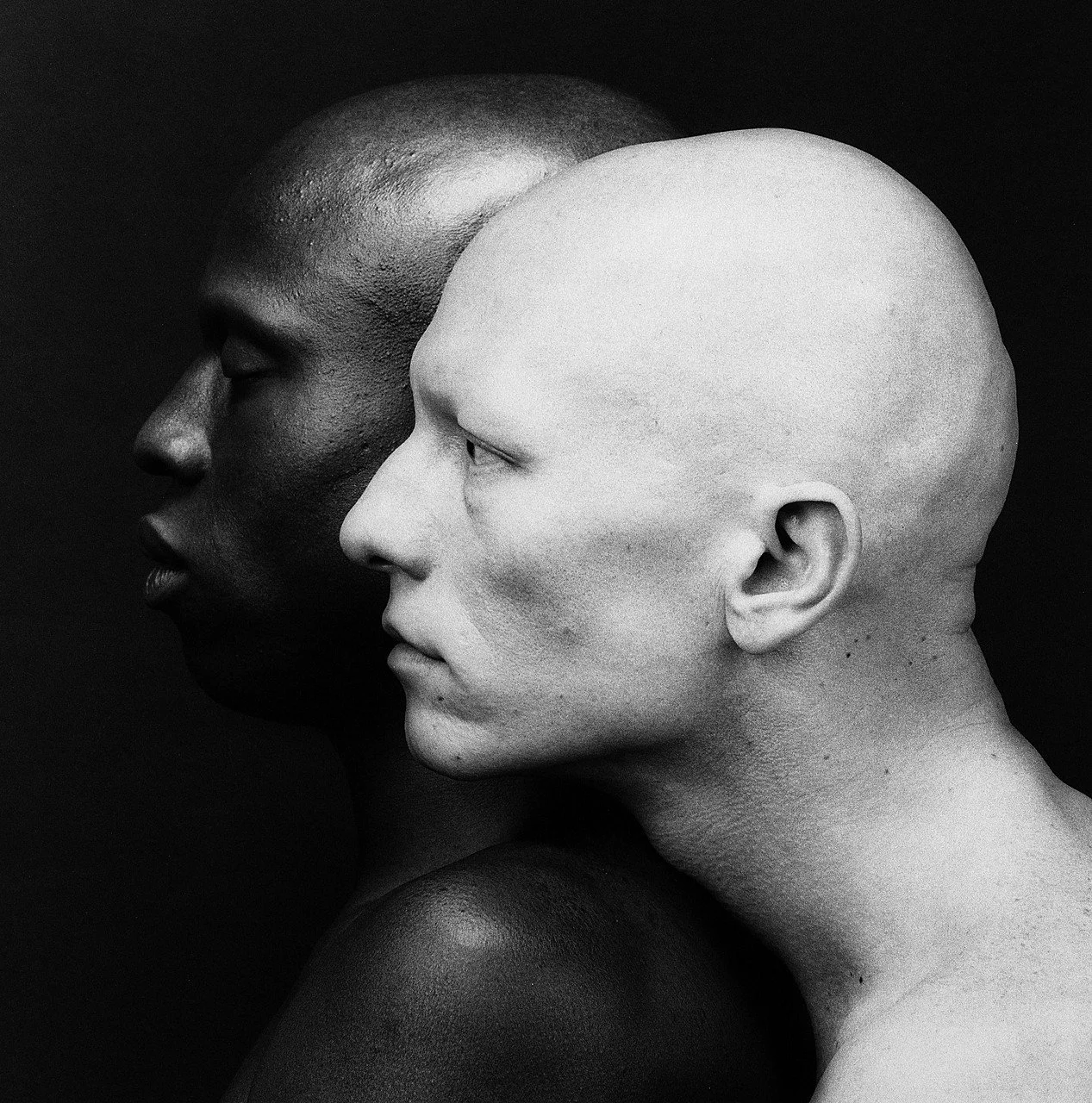

Frank Diaz, 1980 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

Calla Lily, 1987 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

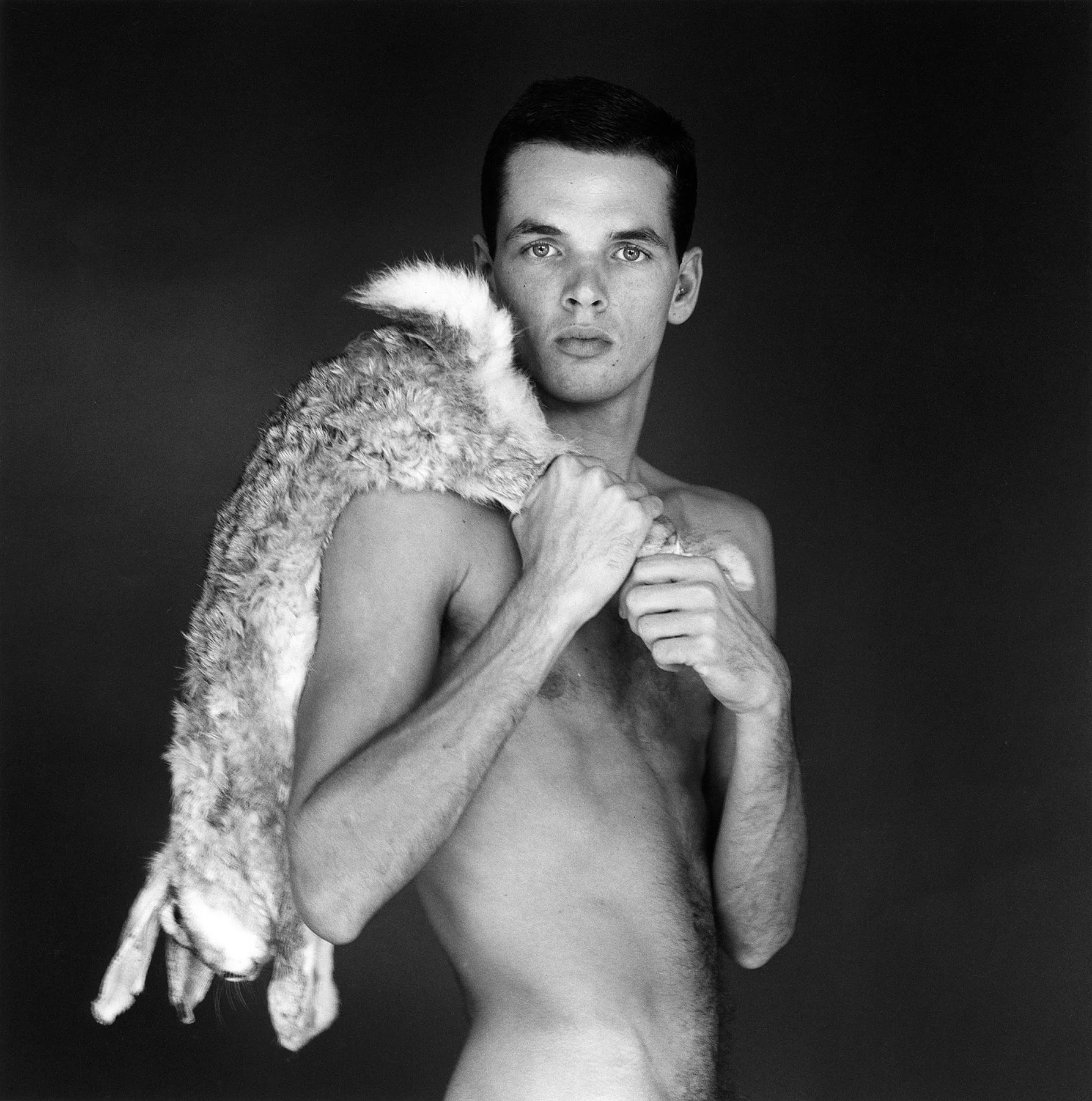

Peter Reed, 1979 credit The Mapplethorpe Foundation

Protest of the cancellation of "Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Moment," June 30, 1989, Washington, D.C. (Frank Herrera)

Robert Mapplethorpe and Jay Johnson 1970 Credit: Valerie Santagto

Lately, I can’t help but think of the Kennedy Center. (I can’t bring myself to write the new name.) I’m proud of the artists who have withdrawn in protest, reminding all of us that what is happening now isn’t right either. I can only imagine how agonizing those decisions must be. Some major acts can simply relocate to another city or venue. But I’m especially moved by the artists who clawed their way up to the level of performing there, only to have a lifelong dream tainted or postponed, perhaps forever. That’s what skin in the game looks like.

I feel this for many other professions not limited to the arts. Any career where in normal times being asked by your president to serve in a role you’ve trained for your entire life would normally be a crowning achievement, but under this administration your achievement comes with an asterisk. You will forever have to defend the good of your efforts to separate them from the harm this administration has inflicted.

In our frame shop, we’ve framed dozens of bills signed by many presidents over the years. Often the real labor behind those documents comes from skilled, passionate people working quietly and earnestly. In this current cycle, clients sometimes lower their voices and tell me that despite the name at the bottom, this particular bill will truly help people in need.

I believe them*

SEE ALSO: The Luxury of Boredom