Everyone Gets A Trophy But You

I write this on Mother’s Day and like the holiday and everything associated with motherhood, it is a story of deep joy and unforgettable pain. It’s all true, and even if the exact events didn’t happen to you and your family, I hope that many notes of this story will ring true to you.

For almost seventeen years I’ve tried to write a part of our story in my head. I’ve tried to make sense of our narrative. We had a son. He was diagnosed with autism. Now what? Why us? Will he be okay? Why won’t anyone listen to my concerns? How many times can I search the Internet, or quiz other parents, searching for hopeful stories? Today, I write my own hopeful story. And my hope is you come away with a better understanding of unseen disabilities, empowered and, educated to fight for those who are so often misunderstood.

Maybe it was the time I was “roadkill,” a term that stuck with me after watching that scene from Sex and the City when Heidi Klum literally steps over Carrie Bradshaw after she trips on the runway in a fashion show. I was Carrie in a real-life scenario, when another mom, holding her congenitally neurotypical easy kid, stepped over me in the hallway of our first of many preschools. I was attending to an inconsolable three-year-old mid-tantrum over forgetting his toy truck at home. If he could have talked, he would have told me why he needed it so badly and that he was frustrated, but he didn’t talk until he was four years old. So yes, it was that roadkill moment when I first felt utterly isolated in my fight for my neuro-atypical kid. I knew something was different about him. Something just wasn’t right, I felt it in my gut. He always seemed tormented and not as engaged as other babies. But pediatrician after pediatrician told us he was fine, normal, and that his delays were typical. The perspective of roadkill is not one I’d wish on anyone. You feel unseen, powerless, and fighting for a chance.

“He’s a boy,”

“He will catch up to the girls in speech, they just develop faster.”

My peers tried to console me. I listened. I kept quiet, even though I had worked as a developmental pediatric physical therapist, and knew these predictions were not so much based in reality as much as their desire to make it all better for us, for him, for them.

I was right, turns out my kid was atypical all along. He was officially diagnosed, then undiagnosed, then diagnosed again with autism.

I’ve started and stopped writing this piece so many times. I have the version I want him to read and the versions I’ve trashed so that he can never see what a mother would put on paper. Each time I write, I think about the purpose. Why do I write this piece about my son? What do I want to say, but more importantly why do I even want to say it? And as I have healed and healed again over the past seventeen years, and I continue to as my son enters his last childhood year, today, I finally have my answer. I want you to know this:

To be human is to try to experience what it’s like to be treated as less than human.

I have struggled to find my peace in finding out why my son has autism. I am still so in denial that I rarely say that word in my head or with my mouth, much less write it down for public consumption. But maybe the answer is this: A higher authority is helping me be more human.

Here is one of the many stories of the fight for my son to be seen:

Even a well-intentioned school doesn’t always do the right thing. We can always improve and grow. One particular school ended up changing their award ceremonies because of him. This was a happy conclusion. But, It was also my saddest moment, and my proudest moment.

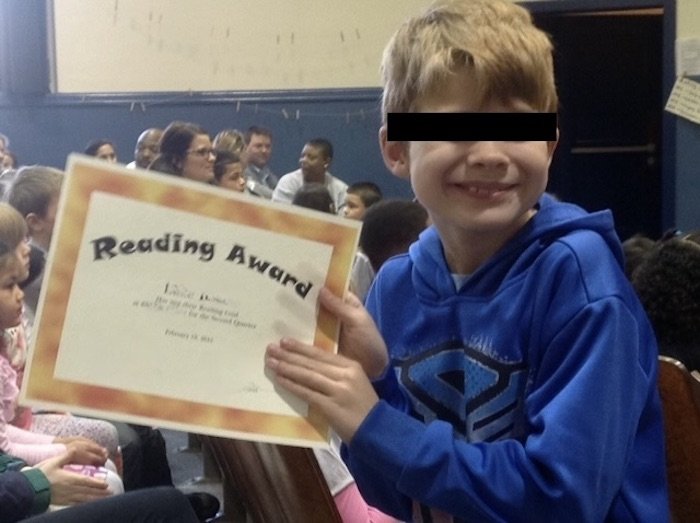

It started in second grade. The school had report card assemblies where kids received two standard awards: Reading Award and Citizenship Award. By standard I mean, most kids got these awards…the keyword being “most.” One day in second grade he came home with the announcement that he would be receiving the Reading Award only. I wondered why he would not be getting the Citizenship Award this quarter so I contacted his second-grade teacher who wouldn’t budge on the subject, “He did not earn the grades required to receive the Citizenship Award.”

He was perfectly happy with receiving the reading award. But I was not.

When I kept inquiring, I was directed to his Special Education Case Manager, who echoed the teacher's statement. Yes, my son had a lengthy IEP (Individualized Education Program) which is a legal document developed as a team effort (including parents) to ensure a child is taught to their abilities within the state they reside. Meaning, the Commonwealth of Virginia is required by law to educate children regardless of their abilities and to the level of their potential. In my son’s case, his kindergarten teacher and school psychologist first suspected he had autism. Therefore, the school absolutely supported him by giving him the tools he needed outlined in his IEP.

Which brings me to my response. Why was my son not receiving this Citizenship Award this time around, even if he had an IEP? Feeling unaware and uninformed, I went to the awards ceremony, sat in the front row, and took notes. When the ceremony concluded, I was both informed and aware. Out of the entire second-grade class, only five (5!) children did not receive the Citizenship Award. Okay, I can feel my heart pounding out of my chest. I need to stop and take some deep breaths.

Five children walked down to accept their awards after their names were read over a speaker system in the auditorium in front of our school community. So five kids received only one award while the rest of the hundreds of kids received two awards including one that deemed them a good citizen. For the unfortunate five, how does that look to their peers? Were those five children, including my son, less than citizens? Were they bad citizens? If I were a kid, I wouldn’t want to be around those “bad citizens”. While watching the ceremony unfold before me, one child even needed an assistant to walk him to the front to receive his award. So clearly these kids may not have had the tools to receive the grades to enable them to be “good citizens”.

These are the criteria used to determine the Citizenship Award. This happens to be the same list of challenges listed in my son’s IEP.

Even though this was a good school, they couldn’t help us. Again, roadkill. But this time I was not going to let them step over me, so we turned to an educational advocate and her response was so simple, “Five kids did NOT get the Citizenship Award? Then only FIVE kids should receive the award. Otherwise, the award system does not make sense.” Essentially, everyone got a trophy but my son. Instead of highlighting people who excelled, they managed to highlight the people who did not, in their eyes, do a good job. And they highlighted this in front of their classmates, teachers, administrators, and parents. It became less about who received the award, and more about who didn’t: A few kids who had special needs.

But I let it go. Until fourth grade, when it happened again. I contacted his new case manager, to let them know that my son would not be coming in that day. Why? Because I would not allow my child to walk up to a stage and be seen as less than human. And I further exclaimed that I hoped the other parents of the other children who were not receiving the Citizenship Award could be granted the same opportunity to sit out of the ceremony so that their children did not need to walk up on stage to be seen as less than human in front of the entire community. His case manager agreed with my points, she couldn’t tell me that she agreed but I know that she did. Because once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

This time around our educational advocate and I got on the phone with the principal and we were prepared to argue our case for my son. We didn’t even finish making our points before he interrupted us, “He more than deserves this award because he is up against so much more than typically developing children. It is even harder for him to practice good citizenship due to his everyday challenges in school.”

Exhale. Someone had stopped and assisted. No more stepping over us. No longer roadkill.

I am not sure if my son even knows about the famous Citizenship Award fiasco, but I will never forget his enormous smile that day when he ran down the aisle to receive it…slapping high fives along the way.

Although this particular story has a good ending, there are so many more that don’t, I won’t tell those stories just yet.

Some disabilities are obvious. We can see them. We see a person who needs a wheelchair, is missing a limb, or has a service dog. But autism is not always visible. It presents in so many ways on that “spectrum,” from having massive, if questionable, success, a la Elon Musk, to being nonverbal and needing twenty-four-hour assistance. Autism can fly so far under the radar, that you likely have a friend who is on the spectrum, but you don’t even know it. The shame of it can keep those with it quiet, lest they once again be misunderstood. Think for a minute about the person people talk shit about behind their back, likely calling them unaware, annoying, or weird. Maybe they were the awkward, outcast “nerd” on the receiving end of torment in high school. Maybe that simultaneous incessant bullying from peers, coupled with a total lack of being seen by the adults in the room led them to dropping out of school since that forced socialization was so utterly exhausting that their nervous system imploded and they chose peace over chaos. You likely thought they were maybe a deadbeat or a druggy for dropping out. I know I did. Again, it is often unseen and misunderstood. So, what can we do? Listen. Learn. Advocate. Fight. Trust your gut. Believe in humans, don’t step over them.